In northwestern Pennsylvania, the village of Benezette bustles with visitors trying to glimpse the largest wild elk herd in eastern North America. But for the residents of this tiny village there is a greater quest – how did this place get its name?

The name Benezette identifies not only the village but also the surrounding township, created in 1843 when Elk County was formed. Three commissioners from nearby counties were appointed to organize the new county: Timothy Ives Jr., a merchant and legislator from Coudersport, James W. Guthrie from Clarion County, and Zachariah H. Eddy from Warren County. It was their job to identify the county and township boundaries and to come up with names. Undoubtedly, they had plenty of suggestions from the people of the new county. The county itself was named for the “noble animal which, upon arrival of the first settlers, in large droves had a wide range over this forest domain.” [1] Some townships were named for local landowners (e.g. Benzinger, Ridgway) or geographical features (e.g. Highland, Spring Creek). Others carried on under the names from their county of origin. Before 1843 the village we now know as Benezette was identified simply as “mouth of Trout Run” or by the surname of one of the early families, “Winslow.” How did the commissioners come up with “Benezette?”

There is one story that has been passed down through the decades involving a hungry bear and a kid named Bennie. As related in the Indiana Evening Gazette of 4 November 1931,

During the early settlement of this country many wild animals roamed the woods. A family living there, a member of which was a little fellow named Bennie. The story is related that one day, during the absence of the older members of the family, a bear entered the cabin, grabbed Bennie and dragged him off into the woods. The father followed the bear’s tracks through the snow, and finally returned alone with the staggering news – “Ben-ez-et.”

Sometimes this story stars two brothers, Bennie and Medix. The outcome is still a well-fed bear, but when Medix is asked by his father "What happened?" his reply is "Bennie's et; Medix run." (This version was told by L. James Bauer (1919-2002) of St. Marys to his niece, Bridget Rucki, in the 1980s.) Of course, Medix Run is another feature of the local geography. This amusing story seems to have originated long after the town was named and is certainly part of the town's oral history.

In the 1840s many new people were moving into the area – that’s one of the reasons the new county of Elk was being created. These new folks were part of the great westward expansion of the United States. New territories and states were being considered as America grew. In the west, where territories were becoming states, one issue in particular caused much discussion – Would they be “free” states or “slave” states?

Pennsylvania was the first state to take a stand on slavery. Beginning in 1780 the Pennsylvania assembly established a series of laws designed to abolish slavery by 1850. It was an imperfect process. With the passage of each law, slave traders exploited loopholes - the legislature responded with new laws. There was widespread support for the abolition of slavery especially among the many religious groups drawn to William Penn’s colony by the promise of religious freedom.

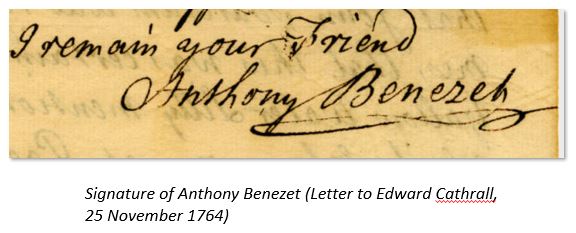

The Society of Friends, also known as Quakers, were prominent in the early government. Their adherence to pacifism often put them in the minority with other Pennsylvanians during the French and Indians War (1754-63) and other conflicts, but they respected the nascent democratic principles of the new republic and found ways to cooperate without compromising their core beliefs. Their commitment to the abolition of slavery was represented by one man, Anthony Benezet, a teacher from Philadelphia.

Benezet[2] was born in France in 1713 but was forced to leave at the age of 2 with his parents when the French government banned all religions except Roman Catholicism. The Benezets and other protestant Christians fled to more tolerant nations in Europe. Many of these religious refugees, known as Huguenots, eventually came to America. Anthony Benezet joined the Quakers in 1727 while the family was in London. They migrated to Philadelphia in 1731 when Anthony was 18. England had already banned slavery and soon after his arrival in Philadelphia Anthony joined with others who were trying to convince Quaker slaveholders that slavery was inconsistent with the beliefs of Christians. He prevailed, and with so many Quakers in the state assembly, anti-slavery laws were soon passed.

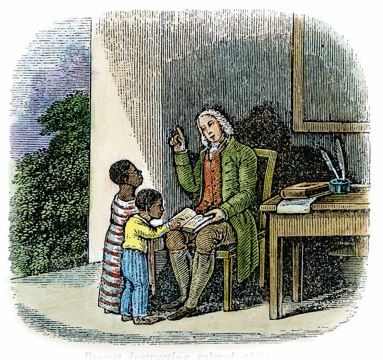

Benezet became well known in Philadelphia as an educator. He was an ardent supporter of school for all, including girls and black children. He believed that all humans were capable of learning and education gave them an advantage. He also believed that all humans deserved to be free. In 1754 he established a school for girls, the first public school for girls in America. He also taught black children, especially those held as slaves, and eventually established a school for them.

In 1775 Benezet and others founded the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, the first anti-slavery society. The outbreak of the Revolutionary War shifted colonial priorities and, despite his Quaker beliefs, Benezet enlisted as a surgeon’s mate. During the British occupation of Philadelphia in the winter of 1778, Benezet stayed in the city to tend to prisoners. Other Quakers also stayed in the city, which caused some supporters of the Revolution to question their loyalty to the cause of independence. After the British evacuated, some Quakers were arrested, but there is no evidence that Benezet was among them.

After Benezet’s death in 1784, Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush reorganized the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully held in Bondage as the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. Benezet’s writings were widely distributed in the American colonies and were influential in the spread of abolitionism. He wrote many pamphlets and letters, but one of his most important works were based on eyewitness accounts documenting the African slave trade.[3] In this first-person history of slavery, the first ever compiled, Benezet also set out both religious and philosophical arguments against slavery.

In early 19th century America, a period of religious fervor and revival, reform movements related to women’s rights, temperance and abolition were spreading, and Benezet’s writings were reprinted and distributed widely. At the time of the creation of Elk County, a new group of settlers, German Catholics, arrived from Baltimore determined to establish a religious community where ownership of property and labor were shared. They were following the example of successful communitarian societies such as Harmony in western Pennsylvania and the Shakers throughout the eastern states. The founding “associations” agreed to share the expenses and labor of establishing their town based on the principles of their faith. They shared a utopian vision, characterized by the Shakers as “heavens on earth.”

For many German immigrants, the movement to abolish slavery was not only a moral issue but also a very personal one. Many had faced war, famine, and persecution in their homeland. They wanted to leave but could not afford the cost of the sea voyage to America. Agents traveled across the German countryside recruiting peasants by promising that their expenses would be paid. All potential migrants had to do was show up at Rotterdam or other ports and report to the ship captain. He made an agreement with them that he would pay their way. In return for this, the passengers agreed to work off their debt, typically over a period of 5 to 9 years. When the ship arrived in America, the ship captains sold these contracts to local landowners who badly needed laborers for their farms. When a servant had worked for the set period, they were said to “redeem” their freedom from the debt and became known as “redemptioners.”

While they were under contract, redemptioners were essentially the property of the master. They were provided food, clothing, and shelter, but they could not leave the property without permission. Redemptioners caught off the property without permission were fined and returned to their masters, where they were punished. There was no guarantee that the same master would purchase the contracts of both a husband and wife, or of their children, and families were often split up. There were no restrictions on the kind of work redemptioners were required to do, or for the number of hours worked per day and there were no restrictions on punishment. The rules that applied to slaves also applied to redemptioners. There was a key difference between this white contract slavery and the forced slavery of Africans – the redemptioners had agreed to the contract of their own accord, and most would eventually be free.

Mathias Benzinger of Baltimore was keenly aware of the situation of redemptioners as an active member of the German Society of Maryland. The German Society was dedicated to helping immigrants who had been victimized by the redemption system. He was contacted by Father Alexander, a priest who had visited the new German settlement known as St. Marys. A year after its founding, the community was faltering. Efforts to work cooperatively were failing. Father Alexander contacted Benzinger, suggesting that this new community could succeed if it was under the control of a strong leader. After a visit, Benzinger agreed and soon acquired more than 60,000 acres in and around the settlement.

There is no evidence that the St. Marys founders were redemptioners, but if they weren't, they undoubtedly knew people who were. That may be what led them to the idea to try and found their own community were settlers relied on each other rather than a master. Benzinger may have seen this as a good alternative to the redemption system. As a reformer, Benzinger was probably aware of the work of Anthony Benezet, and it is likely that others in St. Marys were too. Did they suggest the name “Benezet” to the commissioners for one of the new townships? Had they discussed whether to name their own township Benezet or Benzinger, eventually opting to honor the man who was leading them? Some document may be found one day that can answer these questions, but for now there is no evidence.

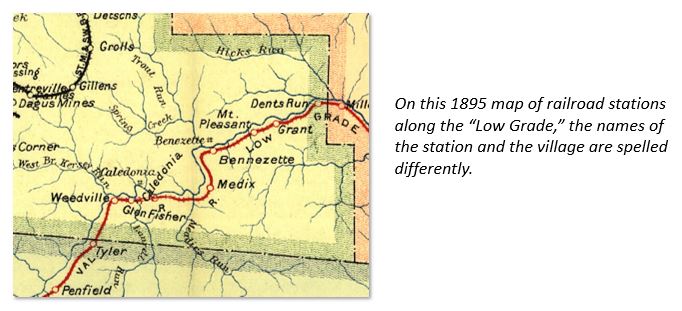

If you look around the village today, you’ll see various spellings of the name. The 18th century reformer from Philadelphia spelled his name B-E-N-E-Z-E-T. If the township was named for Anthony Benezet, how can the difference in spelling be explained? It is an unusual name, by any spelling. It is a family name in France, where it is associated with a saint known for miraculously lifting a large stone to begin the construction of the bridge across the Rhone River at Avignon in 1177. For this feat, St. Benezet is known as the patron saint of bridge builders.[4] Perhaps the county commissioners (or their secretary?), intending to honor Anthony Benezet, were not sure of the spelling, and Benezet became Benezette.

The United States Post Office considers both spellings of the name to be acceptable, even though the spelling on the Post Office is Benezett. According to the Geographic Names Index for the United States, there is only one place named Benezette in the United States and none named Benezet. A search of global place names reveals that there are no other places named Benezette anywhere on the planet. The closest to this unusual name is a township in Butler County, Iowa named Bennezette, and there is an interesting connection to the founders of that place. It seems that William P. Woodworth and Samuel Overturf arrived in Iowa in 1857 and “named the township Bennezette in honor of their native town in Pennsylvania.”[5] People named Woodworth were living along Bennetts Branch as early as the 1830s. Samuel Overturf was elected Benezette Township supervisor in the first election in Elk County in 1846 and there have been many generations of Overturfs in the township since then. It appears that Benezette, PA has a “daughter” in Iowa!

The official spelling, as seen on maps of the US Geological Survey, census records and other public documents is B-E-N-E-Z-E-T-T-E. No matter how it’s spelled, with one or two Ns or Ts or an E at the end, the name is likely a tribute to the man who fought for social justice so long ago. That may be what those first commissioners back in 1843 intended, and even though we may never know for sure, it’s a great name to represent a great place in 21st century America. Benezette – the one and only!

[1] Egle 1876, An Illustrated History of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, p. 682

[2] The name Benezet was accented in French: Bénézet. It was pronounced something like this: bay-nay-zay. When the family moved to Philadelphia, they dropped the accents and the English-speakers of Philadelphia probably pronounced the name somewhat like we do today: be-ne-zet.

[3] Benezet 1771, Some historical account of Guinea . . . with an inquiry into the rise and progress of the slave trade.

[4] The bridge, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is memorialized in a French song that was popular in the 16th and 17th centuries and is still known to many French language students (“Sur la pont d’Avignon”).

[5] History of Butler and Bremer counties, Iowa, 1883, page 480.