In the Illustrated History of Pennsylvania . . . by William H. Egle (1880), local historian John Brooks of Sinnemahoning described this find in Sterling Run (page 483).

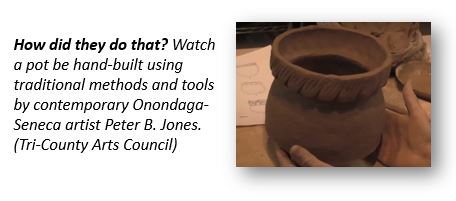

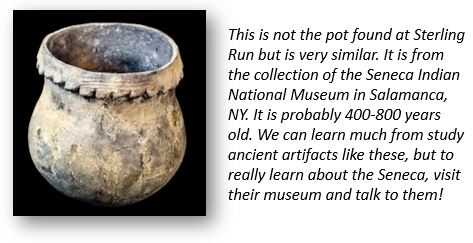

In the year 1873 excavations were being made for a cellar under the post office building, at Sterling Run, in this county. The building had been removed from its former site about forty feet, and hence the demand for the excavations for a cellar under the building at its new site. Mr. Earl, the proprietor of the grounds, in making these excavations found human bones, and proceeded the more carefully to continue his excavations, which, when completed, disclosed seventeen skeletons, evidently of Indian origin. All except two were of ordinary grown stature, while one measured over seven and a half feet from the cranium to the heel bones. The bones had all remained undisturbed. They lay with their feet toward each other in a three-quarter circle, that is, some with their heads to the east, and then north-easterly to the north, and then north-westerly to the west. There had been a fire at the centre, between their feet, as ashes and coals were found there. The skeletons, except one smaller than the rest, were all as regularly arranged as they would be naturally in a sleeping camp of similar dimensions; the bones were many of them in a good state of preservation, particularly the teeth and jaw-bones, and some the the leg-bones and skulls. The stalwart skeleton had a stoneware or clay pipe between his teeth, as naturally as if in the act of smoking; by his side was found a vase or urn of earthenware, or stoneware, which would hold about a half gallon. This vessel was about one-third filled with a somewhat granular substance like chopped up tobacco stems or seeds. The vase had no base to stand upon, but was of the gourd-shape and rounded; its exterior had corrugated lines crossing each other diagonally from the rim. The rim of the vase had a serrated or notched form, and the whole gave evidence that it had been constructed with some skill and care.

Seneca Iroquois National Museum and Onöhsagwë:de’ Cultural CenterCultural Center, Salamanca, NY

The skeletons were covered about 30 inches deep, 24 inches of which was red shale clay, or good brick clay. The top six inches was soil and clay, which, doubtless, had been formed from the decayed leaves of the forest for centuries. This ground had been heavily timbered. When the first clearing was made upon it in 1818 there had not grown immediately over or upon this spot any large trees, as no roots of trees had disturbed the relics, yet the timber in the immediate vicinity had been very large white pine and oak. This spot had been plowed and cultivated since 1818 and had been used as a garden for the last preceding ten years. I visited the ground and examined the locality and position of the skeletons. One, the smallest, had been in the erect or crouched position, in the north-west corner of the domicile. The most reasonable theory is that this was their habitation: that their hut had been constructed of this clay, as the surrounding grounds were gravelly, as was also the bottom of this spot. It would seem that the gravel had been scooped away, or had been excavated to the depth of two feet, and that there had been a hut constructed of clay over the excavation, and that while reclining in their domicile some electric storm had in an instant extinguished their lives, and at the same time precipitated their mud or clay hut upon them, thus securing them from the ravages of the beasts of the forest.

Brooks assumes that the 17 people were all buried at the same time. We have no way of verifying this, but an archaeologist would also consider that they were not buried at the same time, but instead were buried over a period of time, perhaps several years or more. Think about it - to lose 17 members of a small community at one time would be very unusual, unless there was an illness or an attack by others. Brooks did not relate any trauma to the remains (for example, broken bones, cracked skulls, missing body parts) that might be the result of violence. We don't know if that's true or if Brooks just did not recognize these injuries. If it is true, then we might conclude a disease was the cause of death. But we don't have enough information to conclude that, either. It would be helpful to have a biological anthropologist conduct a forensic analysis of the remains to determine more about who these people were. Men? Women? Old? Young? It appears that there might be at least one child (". . . the smallest [was buried] in the erect or crouched position"]. Disease tends to disproportionately affect the most vulnerable members of a community, typically the very young and the very old, so if this community was distressed by some infection, we would expect to find the remains of the young and the old. But again, we just don't have the evidence to conclude this either.

If people were buried at different times, that could account for the different orientations of the remains. The pottery is our only clue about when the remains were buried. It's form and surface treatment suggest that it was probably about 500 to 1,000 years old. The red clay is interesting. The evidence for houses in Pennsylvania from about 1,000 years ago seem to be bark-covered structures. It's possible that the red clay was the floor of a house, but it might have been a layer added purposely to cover the remains with a low mound. We do have evidence of burial mounds in Pennsylvania along the Allegheny River and even in Elk County, PA. At mound sites, people were often buried over a period of time, then the community decides that it is time to complete the mound (perhaps they are moving from the area) and they might add more material to the mound.

We don't know what the folks of Sterling Run did with the remains of these ancient ancestors in 1873. Let's hope that they were respectfully removed from the construction site and reburied nearby where they they still remain, undisturbed.