In the introduction to his book Extinct Pennsylvania Animals (part 2), published in 1919, folklorist and historian Henry Shoemaker expresses a conservation ethic that was beginning to be popular at the time.

That ten of the larger mammals of Pennsylvania should have been completely exterminated within the borders of our Commonwealth, eight of them—the Panther, Wolf, Pine Marten, Beaver, Fisher, Glutton, Elk and Canada Lynx—within the memory of men now living [in 1916, when he wrote the book], is an appalling statement to place before naturalists and conservationists. That all of these animals were of inestimable value to mankind, either for their flesh, fur, or to preserve the Balance of Animate Nature, or as destroyers of various pests, makes the loss all the more severe on civilization.

If this wanton destruction of harmless creatures is to go on apace, a book on the existing wild mammals of Pennsylvania cannot be written half a century hence. Private greed, that lust for blood money which has been the undoing of so many persons and States, has been responsible for the awful diminution of the wild life of Pennsylvania. Placing animals in politics has been a most potent and complete cause of the destruction of interesting forms of life. When the lumber business waned, due to reckless cutting and waste, the lack of replanting and forest fires, there was a tendency for the mountainous districts to de populate themselves—the drift was towards the cities or towns where there was work.

The crafty political chieftains, scenting a loss of prestige in certain districts, devised a clever scheme to keep the mountaineer vote in the slashings by the passage of laws paying out large sums of money on the scalps of alleged noxious animals and birds. A clever publicity campaign was worked up charging all kinds of misdemeanors to nearly all the animals and birds which remained in the Pennsylvania forests. This same graft is going on in our Western States today. Bounty payments commenced, the poorest class of mountaineers were baited by the lure, and remained in the denuded areas trapping for bounties.

It was a mean living, especially at the expense of the taxpayers and agriculturists, who would surely suffer by the loss of so many insect and rodent devouring creatures.

After one year of the "scalp act" of 1885[1], the farmers and fruit-growers rose as a body and demanded the repeal of the section relative to hawks and owls. It was taken off the Statute Books, but not until hundreds of thousands of dollars of the people's money had been squandered, and insect pests threatened to make agricultural Pennsylvania a desert like birdless Italy. A few years ago the bounty on hawks and owls was again inserted in the scalp act, but again repealed.

But the bounties on animals have climbed higher and higher, to keep pace with the increased desire of the professional hunters to cut it out and take up honest livings in the towns. The animals to kill have grown fewer and fewer, which is another reason for the increase.

At present the politicians are plundering the hunters' license fund, which ought to be used for game protection and propagation, to the extent of a hundred thousand dollars in bounties, annually, and not a word is raised against this brazen thievery.

The animals of Pennsylvania belong to all the people, they must not be exploited for private or political gain. Is there not a voice of a scientific or learned man or woman who, knowing the facts, will rise up in their behalf and ask the Governor to remove the incentive to their cruel destruction by curtailing or checking the existing bounty law? . . .

After all this blood slaughter and destructiveness are we any better off? Decidedly not. We have the forest fire, the spray pump, the tent caterpillar, the San Jose scale, the Norway rat, the Zimmerman moth, the high cost of living, the poisoned well and the polluted stream, all instead of our cool forests, clear streams, sweet springs and wonderful animal, bird and aquatic life of the old days. Where is the tainted money earned by the political pets and professional hunters—boozed up, of course, along a long lurid lane of vice and crime.

Give us back our wildlife, enlightened generations of the future will demand, but never again in this aeon will mankind see their like. The grand game animals are known only as a memory.

While those of us who enjoy the forests and wildlife of Pennsylvania in the 21st century appreciate Shoemaker's view (and are grateful for it!), it's important to remember that every individual is always a product of their times. The need for conservation went beyond the wildlife to the forest, too.

Shoemaker wrote this when he returned from service following the Great War, which we know today as World War I. American society was in the midst of sweeping changes. The war, a flu epidemic, the rising support of prohibition, voting for women – these were all momentous, and the fact that they happened within the span of several years reflected the new way that Americans were thinking about their society. Politicians like President Theodore Roosevelt and Pennsylvania Governor Gifford Pinchot supported the conservation of the wild places of the American landscape, resulting in park and forestry programs based on the scientific management of natural resources. This was a policy that was not without controversy. American industry was booming and did not want any constraints on its mining, drilling, and lumber operations and the network of transportation needed to support it, especially railroads and highways. With our 21st century benefit of hindsight, we can appreciate their concerns and the movements of the ongoing efforts at conservation.

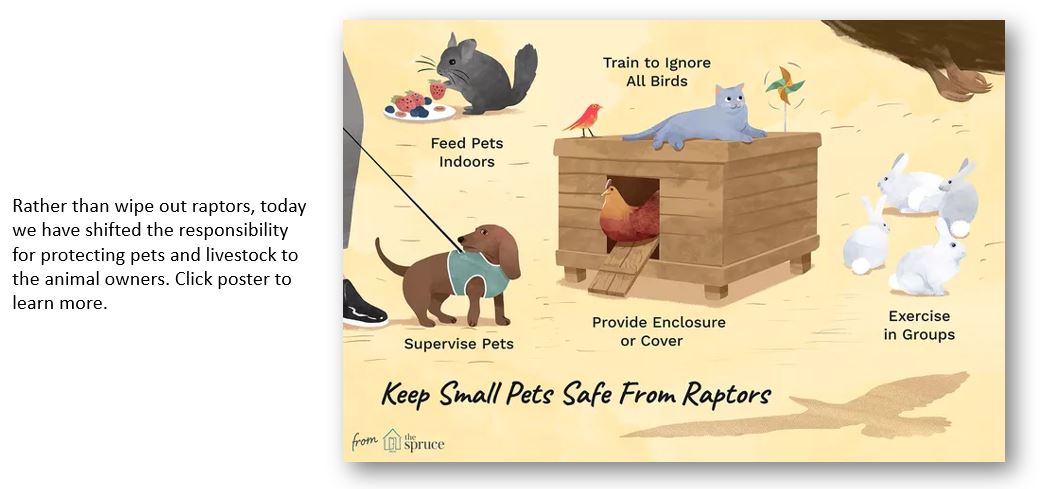

[1] The Bounty or “Scalp Act” of 1885 in Pennsylvania created a list of bountied predators that could be legally killed. The scalps of these animals were worth various amounts of money when turned into the proper authorities. Within two years following the passage of the law, 180,000 scalps were sent to Harrisburg; the bounty paid was 50-cents per scalp (Keith L Bildstein, Raptors as vermin: a history of human attitudes towards Pennsylvania’s birds of prey, Endangered species update, 2001, 18(4). The goal was to remove animals that were dangerous to humans or domesticated animals, and included not only wolves, foxes, bobcats, minks and weasels but also raptors such as goshawks, sharp-shinned hawks and great horned owls. By 1914, raptors were removed from this list (Joe Kosack, In Kalbfus we trusted, PA Game News July 2020). See also Bounties: the rise and fall by Kosack in PA Game News, February 2020.