We don't have much documentation of what life along Bennett's Branch of the Sinnemahoning was like at the time of the French and Indian War or the American Revolution, but we do have stories from people who settled in the surrounding area. It's likely that life for those early families (Winslows, Johnsons, Moreys and others) was very similar.

Sherman Day (1843, Historical collections of the State of Pennsylvania) collected these reminisences through interviews and historical documents.

Clearfield County (Day 1843: 236-7)

On the site of the present county seat [Clearfield], there was an old Indian town by the name of Chinklacamoose, or, as some have it, Chinklacamoose’s old-town. Clearfield was for many years called Oldtown, and is still [in 1843] by many of the older settlers. A small stream north of the town still retains the name of Chinklacamoose creek, though sometimes shortened to ‘Moose creek. The Seneca Indians of Cornplanter’s clan used often to hunt around Chinklacamoose.

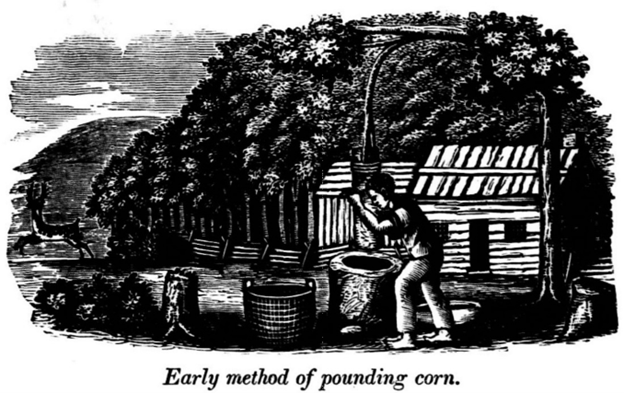

Arthur Bell and Daniel Ogden, with his son Matthew, then a lad of 18, came up the West branch [of the Susquehanna] in the spring of 1796, bringing with them the simple tools of the pioneer, with a few potatoes and seeds for their first crop. Bell settled a few miles above Clearfield; Odgen near the mouth of Chinklacamoose creek, where, after a year or two, he built the first mill in the county. They suffered various trials and hardships in opening their new homes. Provisions were very scarce, and the nearest settlement was at Bald Eagle, about 140 miles by water [near present-day Lock Haven]; nothing of any weight could be brought by land. Mr. Bell was at one time compelled to travel this whole distance to get a plough point repaired; poling his canoe patiently up the stream, loaded with his irons, and some provisions, his provisions by some accident were wet. The first time he used his plough, the point broke again, and his toilsome journey was in vain. For some time before the mill was built, they pounded their corn in mortars. Their route by land was the old Indian path across the mountains by the Snow-shoe camp to Milesburg. Mr. Ogden once travelled this route in winter with show shoes, requiring 2 ½ days to reach Milesburg, 33 miles.

Among the older residents was John Bell, a brother of Arthur. He had been an old revolutionary soldier, and when the conflict was over he sought an asylum with his brother. From his very diminutive size he commonly bore the name Johnny Bell. From the force of military habits, or for fear of losing the art of fighting by disuse, he used to have an occasional quarrel with the friendly Indians about the settlement, and usually came off triumphant. In a frolic of this sort two of them attempted to drown him, but he came very near drowning both of them.

Being an old bachelor, he was rather whimsical, and would sometimes get in a pet; in some such mood he once quit his brother’s house, and encamped in the woods, determined to remain there; but Greenwood Bell, his nephew, one day made him a call at his camp, picked the little fellow up, slung him over his shoulder, and toted him off home, where he was afterwards contented to remain.

Potter County (Day 1843: 601-2)

In 1811 Benjamin Birt moved to what we now today as Potter County. Some parts of his story may sound familiar to modern campers.

I moved in on the 4th May, 1811, and had to follow the fashion of the country for building and other domestic concerns – which was rather tough, there being not a bushel of grain or potatoes, nor a pound of meat, except wild, to be had in the county; but there were leeks and nettles in abundance, which, with venison and bear’s meat, seasoned with hard work and a keen appetite, made a most delicious dish. The friendly Indians of different tribes frequently visited us on their hunting excursions. Among other vexations were the gnats, a very minute but poisonous insect, that annoyed us far more than mosquitoes, or even than hunger and cold; and in summer we could not work without raising a smoke around us.

Our roads were so bad that we had to fetch our provisions 50 to 70 miles on pack-horses. In this way we lived until we could raise our own grain and

Our roads were so bad that we had to fetch our provisions 50 to 70 miles on pack-horses. In this way we lived until we could raise our own grain and

meat. By the time we had grain to grind, Mr. Lyman had built a small grist-mill; but the roads still being bad, and the mill at some distance from me, I fixed an Indian samp-mortar to pound my corn, and afterwards I contrived a small hand-mill, by which I have ground many a bushel – but it was hard work. When we went out after provisions with a team, we were compelled to camp out in the woods . . .

The first winter, the snow fell very deep. The first winter month, it snowed 25 days out of 30; and during the three winter months it snowed 70 days. I sold one yoke of my oxen in the fall, the other yoke I wintered on browse; but in the spring one ox died, and the other I sold to procure food for my family, and was now destitute of a team, and had nothing buy my own hands to depend upon to clear my lands and raise provisions. We wore out all our shoes the first year. We had no way to get more – no money, nothing to sell, and but little to eat – and were in dreadful distress for the want of the necessaries of life. I was obliged to work and travel in the wood barefooted. After a while, our clothes were worn out. Our family increased, and the children were nearly naked. I had a broken slate that I brought from Jersey Shore. I sold that to Harry Lyman, and bought two fawn-skins, of which my wife made a petticoat for Mary; and Mary wore the petticoat until she outgrew it; then Rhoda took it, till she outgrew it; then Susan had it, till she outgrew it; then it fell to Abigail, and she wore it out. [Women wore a white shift, or chemise, under their clothes. The petticoat was a skirt worn over the shift. To see examples of women's clothes from this time period (and many others), check out Peggy's Closet.]